4 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)

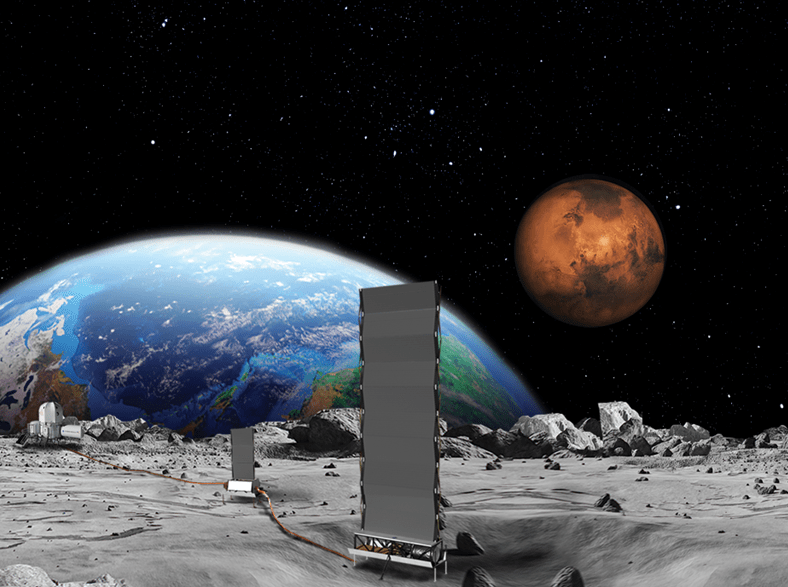

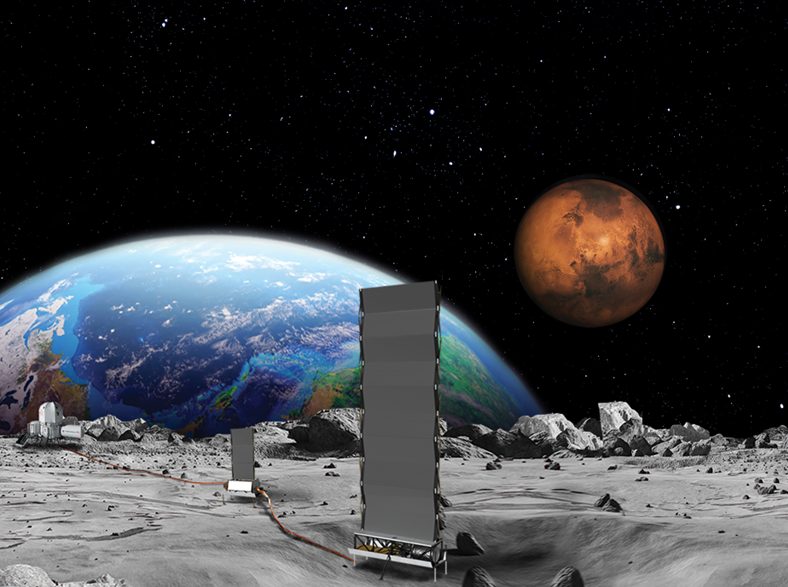

NASA is wrapping up the initial phase of its Fission Surface Power Project, which focused on developing concept designs for a small, electricity-generating nuclear fission reactor that could be used during a future demonstration on the Moon and to inform future designs for Mars.

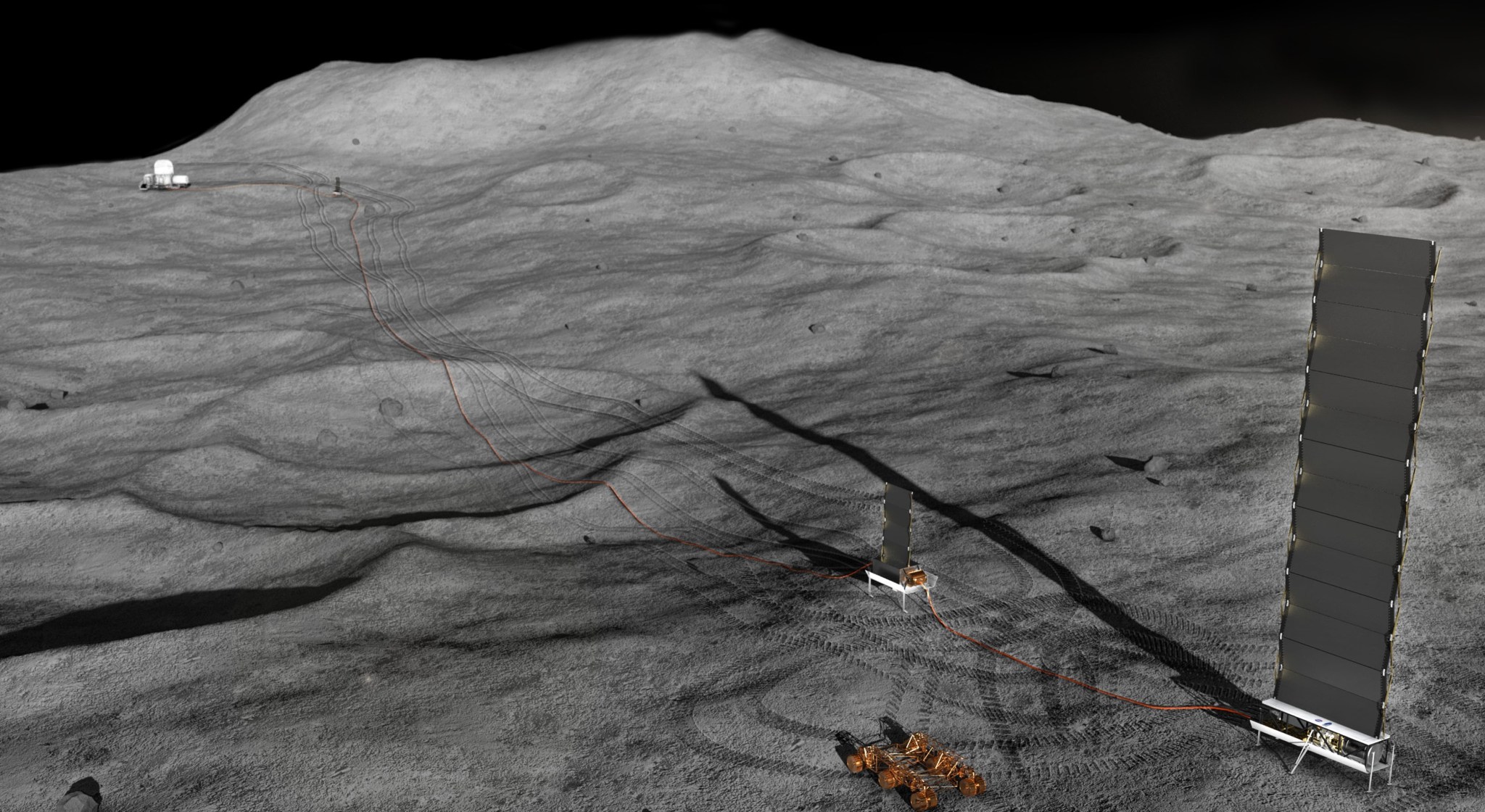

NASA awarded three $5 million contracts in 2022, tasking each commercial partner with developing an initial design that included the reactor; its power conversion, heat rejection, and power management and distribution systems; estimated costs; and a development schedule that could pave the way for powering a sustained human presence on the lunar surface for at least 10 years.

“A demonstration of a nuclear power source on the Moon is required to show that it is a safe, clean, reliable option,” said Trudy Kortes, program director, Technology Demonstration Missions within NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “The lunar night is challenging from a technical perspective, so having a source of power such as this nuclear reactor, which operates independent of the Sun, is an enabling option for long-term exploration and science efforts on the Moon.”

While solar power systems have limitations on the Moon, a nuclear reactor could be placed in permanently shadowed areas (where there may be water ice) or generate power continuously during lunar nights, which are 14-and-a-half Earth days long.

NASA designed the requirements for this initial reactor to be open and flexible to maintain the commercial partners’ ability to bring creative approaches for technical review.

“There was a healthy variety of approaches; they were all very unique from each other,” said Lindsay Kaldon, Fission Surface Power project manager at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. “We didn’t give them a lot of requirements on purpose because we wanted them to think outside the box.”

However, NASA did specify that the reactor should stay under six metric tons and be able to produce 40 kilowatts (kW) of electrical power, ensuring enough for demonstration purposes and additional power available for running lunar habitats, rovers, backup grids, or science experiments. In the U.S., 40 kW can, on average, provide electrical power for 33 households.

NASA also set a goal that the reactor should be capable of operating for a decade without human intervention, which is key to its success. Safety, especially concerning radiation dose and shielding, is another key driver for the design.

Beyond the set requirements, the partnerships envisioned how the reactor would be remotely powered on and controlled. They identified potential faults and considered different types of fuels and configurations. Having terrestrial nuclear companies paired with companies with expertise in space made for a wide range of ideas.

NASA plans to extend the three Phase 1 contracts to gather more information before Phase 2, when industry will be solicited to design the final reactor to demonstrate on the Moon. This additional knowledge will help the agency set the Phase 2 requirements, Kaldon says.

“We’re getting a lot of information from the three partners,” Kaldon said. “We’ll have to take some time to process it all and see what makes sense going into Phase 2 and levy the best out of Phase 1 to set requirements to design a lower-risk system moving forward.”

Open solicitation for Phase 2 is planned for 2025.

After Phase 2, the target date for delivering a reactor to the launch pad is in the early 2030s. On the Moon, the reactor will complete a one-year demonstration followed by nine operational years. If all goes well, the reactor design may be updated for potential use on Mars.

Beyond gearing up for Phase 2, NASA recently awarded Rolls Royce North American Technologies, Brayton Energy, and General Electric contracts to develop Brayton power converters.

Thermal power produced during nuclear fission must be converted to electricity before use. Brayton converters solve this by using differences in heat to rotate turbines within the converters. However, current Brayton converters waste a lot of heat, so NASA has challenged companies to make these engines more efficient.

The Technology Demonstration Missions program manages Fission Surface Power under NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.